The field of haptics delves into the sense of touch through our mechanoreceptors under the skin. It’s used across various applications to convey information or sensations to the user. This ranges from simple vibrational feedback of a control button to complete immersion in a realistic tactile environment, enabling the perception of textures, shapes, and resistances, thereby enriching the sensory experience.

In this context, our specific focus lies on the vibrational domain, a part of the broad haptic field.

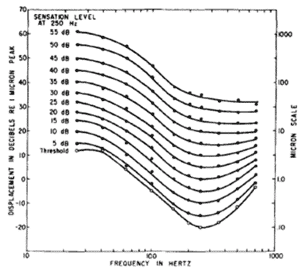

Into their article [1], Verrillo, R. T., Fraioli, A. J., and Smith, R. L. highlighted the detection threshold curves and iso-intensity curves for vibrations on the finger as shown in Figure 1.

Notably, the perceptible frequency range extends from 20Hz to almost 1000Hz with maximum sensitivity around 250Hz.

Several specific drivers allow to generate vibrations in this range, as the Eccentric Rotating Mass (Figure 2), a motor that rotates an off-center mass to create vibrations. While easy to operate with just a DC power input, its limitation comes from the coupling between the vibration frequency and its amplitude (e.g. it is impossible to increase the amplitude of vibration without changing the rotation frequency).

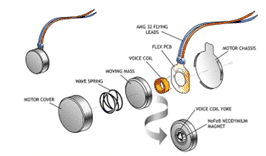

To overcome this limitation, linear resonant actuators (Figure 3) have been invented. With a construction similar to the electrodynamic loudspeaker, it becomes possible to generate more complex signals.

Such drivers enable the generation of a frequency-dependent force, that relies on the acceleration of the mobile part following the well-known equation Force = Mass * Acceleration.

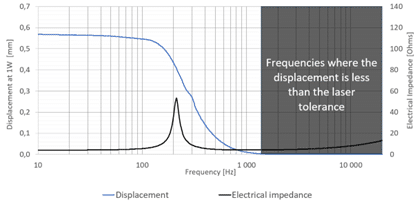

This acceleration can be easily deduced from a measurement of the mobile part’s displacement using a laser sensor (Refer to Figure 4.a). Resulting signal depicts displacement against frequency, showcasing maximum amplitude below the driver’s resonance frequency (Refer to Figure 4.b).

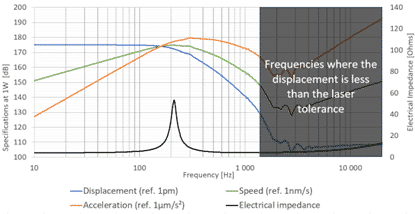

Acceleration can then be deduced through simple mathematical derivatives, as illustrated in Figure 4.c. For easier visualization, the results are presented in decibels.

Figure 4 – Experimental setup using a Displacement laser (c) and results either in SI units (a) or decibel units (b). Additionally, the deduced speed and acceleration are also shown (b).

Review by:

Frédéric Fallais, Acoustic Application Engineer

Arthur Di Ruzza, Acoustic Technician

Sources :

[1] Verrillo, R. T., Fraioli, A. J., and Smith, R. L.. “Sensation magnitude of vibrotactile stimuli”, Perception & Psychophysics, 6(6):366–372 (1969)